Automatic language translation

Our website uses an automatic service to translate our content into different languages. These translations should be used as a guide only. See our Accessibility page for further information.

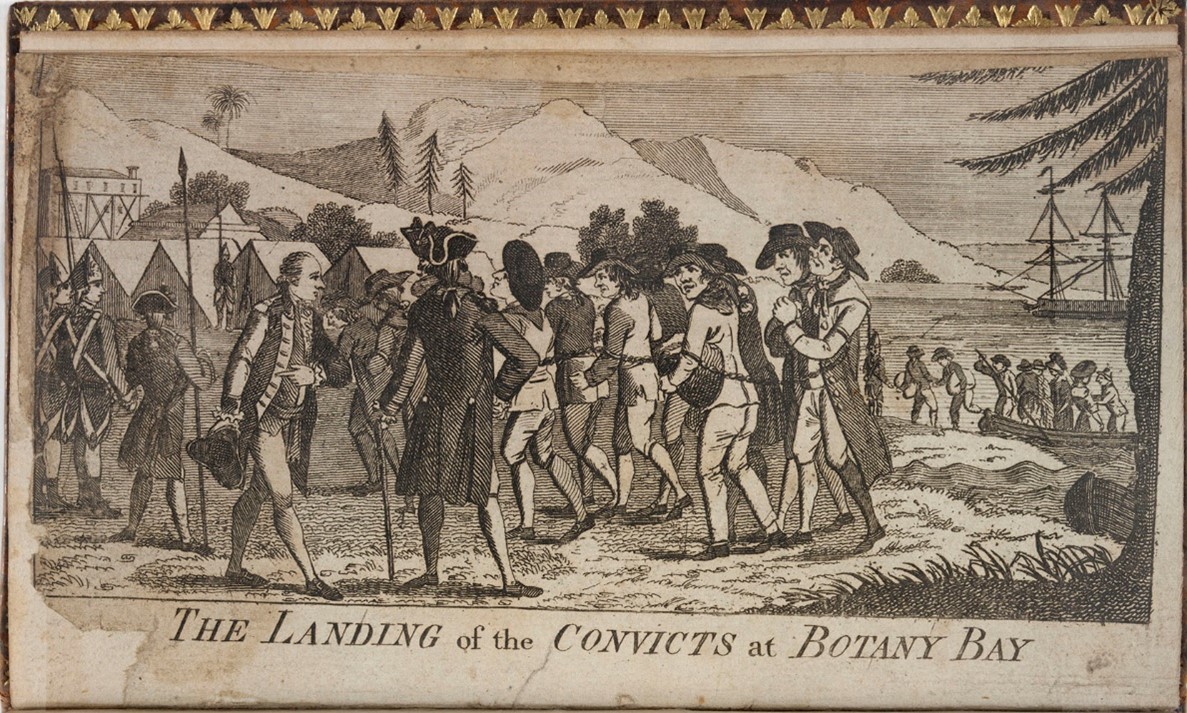

Corrective services played a major role in the first 50 years of New South Wales' history due to its establishment as a vast prison.

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, Britain was forced to find ways of dealing with criminals other than transporting them to the United States.

In 1786, it was decided to send them to New South Wales. The government's instructions to the first governor of the new penal colony, Captain Arthur Phillip, were few and scrappy.

Initially, the convicts were housed in tents on one side of Sydney Cove and the marines who guarded them were on the other. For many years there were no quarters for convicts and they often had to find private lodging in the town. Convicts worked part of the day for the government and were free for the rest to find paid work to earn rent for their lodging.

As the demand for labour in the colony grew, the system of assigned service developed. Convicts were assigned to masters and largely lived under their control.

Assigned service ended following a large influx of convicts after the Napoleonic wars and was replaced by chain gangs in 1826. During this period the convicts worked in heavy chains, including a neck collar, and were punished on the spot for trivial offences.

In 1840, the British government ended transportation to New South Wales as it believed the colony had become too "settled" and "civilised" to be useful as a penal settlement.

In 1840, Alexander Maconochie became the Governor of Norfolk Island, a prison island where convicts were treated with severe brutality and were seen as lost causes.

Maconochie was a reformer who treated prisoners much as we do today. He believed that cruelty debases both the victim and the society inflicting it, and that punishment for crime should strengthen a prisoner's desire and capacity for reform. Sentences should be served in progressive stages, one of which involved membership of a working party where each was held responsible for the conduct of the others. Convicts should not be deprived of self-respect.

These practices do seem to have encouraged rehabilitation, but were so far ahead of their time that Maconochie was derided. Most people at the time believed the purpose of imprisonment was simply to punish. He lost his job after just four years, but a century later he would come to be seen as an inspirational figure in the history of prisons.

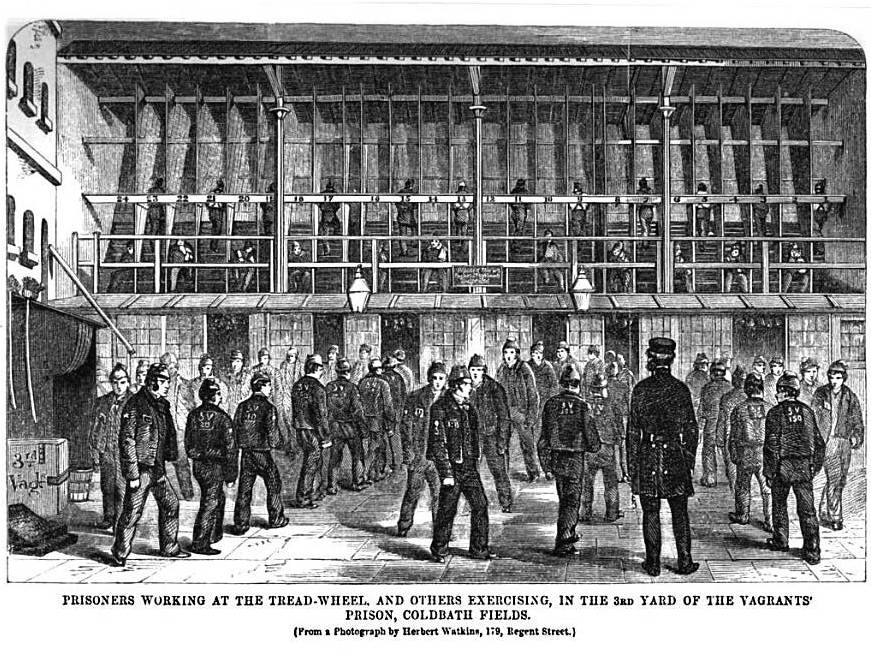

Strict new regulations issued in 1867 were influenced by the British Prisons Act 1865, was a result of public demand for more severe measures following an increase in street violence in England in the early 1860s.

The aim of the British Prisons Act was deterrence through fear. The House of Lords used the phrase "hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed".

The regulations introduced in NSW in 1867 were designed to put into effect the "separate and silent" system which had evolved in British prisons, where inmates were kept in single cells and not allowed to communicate with each other.

Under the new regulations, all prisoners served one-twelfth or 12 months (whichever was the lesser) of their sentences in this separate system.

In 1865, the government made Berrima a model prison with a view to introducing the separate treatment system. Unmanageable prisoners from other prisons were sent there for "coercion", as would occur with Grafton a century later.

Allegations of cruel treatment at Berrima Gaol led to a Royal Commission into the gaol in 1878. The two Berrima Gaol practices highlighted for their cruelty were spreadeagling and the gag. The Royal Commission concluded:

"It must be admitted that the chaining of a man to the walls of a cell is a barbarous means of punishment, which should not be tolerated as a means of punishment, and there should be no necessity for resorting to it as a method of restraint.

"We desire to see no further instance of the chaining of a prisoner to the walls of his cell and we beg to recommend that the ring-bolts be removed."

The Commission recommended strict limitations on the use of the gag, an instrument designed to temporarily silence difficult prisoners.

Despite the harsh and severe methods used in this era, there was one experiment of note in NSW. This was the construction of an experimental prison at Trial Bay, near Kempsey, on the Mid North Coast. The prison was designed to provide useful work and a certain amount of freedom for prisoners who were fit, well-behaved and within seven years of the end of their sentences.

The prisoners were paid wages and their wives and families were allowed to visit them. They were engaged in the construction of a breakwall designed to provide a harbour of safe refuge for ships on the coastal route. The experiment was later abandoned.

During the second half of the 19th century, the NSW prison system, closely followed the trends and practices of the British system. In 1894 Herbert Gladstone, the Under Secretary of State, was appointed by the British government to conduct a committee of inquiry into the British prison system.

Known as the 'Gladstone Committee', the findings had important repercussions for NSW prisons. The committee concluded that conditions of imprisonment at that time did not lead to any moral reform or change in behaviour. On the contrary, it reduced the prisoner's capacity to cope with the demands of life upon release from prison.

The committee recommended that the British system should be more flexible, adaptable to individual conditions and needs, aimed at reform and at turning prisoners out of prison better, physically, and mentally, than when they went in.

The committee also recommended the abolition of servile and punitive labour, and a focus towards productive and rehabilitative work. The committee dismissed the idea that cellular isolation had any reforming effects.

In 1895, Captain Frederick Neitenstein, a seaman who had been in charge of two training ships for truant and delinquent boys, was appointed chief administrator of NSW prisons. He closely studied the report of the Gladstone Committee.

During the following 14 years while he oversaw NSW prisons, Neitenstein displayed an enlightened and humane attitude to the treatment of offenders. He was particularly concerned about the practice of placing the mentally disturbed, alcoholics and the homeless in prisons. (Many of those gaoled for drunkenness in this period, such as the writer Henry Lawson, would today be treated in hospitals for the disease of alcoholism.)

Neitenstein was also disturbed at the mass imprisonment of defaulters, first offenders and petty offenders, as well as the sick, the infirm, the aged and even children. He continually argued against "unnecessary gaoling", even though he, like all prison bosses, had no control over who the law and the courts sent to prison.

The main changes during Neitenstein's term of office were the grading and use of specialised functions for prisons, such as the use of Goulburn Gaol for the confinement of first offenders, the concentration of prisons through the closing of many small gaols, the reduction of the "separate and silent" system, and the introduction of restricted association amongst prisoners, to protect the weak from the strong.

He also pressed for the construction of a separate prison for women resulting in the opening of the State Reformatory for Women at Long Bay in 1909, the year he retired.

As a man of vision, Neitenstein also placed great emphasis on the need to help released prisoners. During his time, elementary examinations were introduced to end the recruitment of illiterate officers and collections of books were built up in prisons so that officers could educate themselves about ideas on crime and punishment.

Other humane changes made during Neitenstein's administration, included an end to the use of dark cells as a punishment, improvements in general hygiene, and a more varied diet for prisoners.

The drive for reform which sprung from Neitenstein's changes continued after his retirement. The most significant developments included the establishment of an afforestation camp at Tuncurry and the opening of a prison farm at Emu Plains in 1914.

Last updated: